- A Series of Unfortunate Events

- Anne of Green Gables

- The Secret Garden

- Harry Potter

- Pippi Longstocking

- The Giver

- Milkweed

- Ballet Shoes

- Great Expectations

Well, by now you’ve probably figured it out – right??? (If you hadn’t yet, the last one gave it away, I’m sure…)

Every single one of these books, many of them enduring classics, features a main character whose parents have – um – gone to the next world.

Tragic, isn’t it?

Or it WOULD be tragic if the books themselves weren’t so terrific because of it.

Why do orphans make such great main characters?

We love these books so much because orphans are forced to fend for themselves. If they do have a guardian, the guardian is often either incompetent, unaware, or simply not emotionally connected to the main character.

And this is GREAT for your story!

Why? Because the very best stories are ones in which the main character rescues himself from the book’s main problem. (What? Your story doesn’t have a main problem??? Eeeeek!)

Don’t rescue them from the tree!

I’m sure you’ve heard the formula before: “in Act One of your story, you have to get your main character up a tree, in Act Two you “throw rocks” at the character, tormenting him to make his life utterly miserable, and then, in Act Three, you get them down again.”

Yet so many writers take this magic formula, apply it to their story, and wonder what went wrong when it flops and dies a gruesome death of its own.

Here’s what went wrong!

If you step in to get them down, I guarantee you the world’s most boring kids’ story. And stepping in, when it comes to a kids’ book, also means letting the characters’' parents step in (Deus ex machina-style) to assist in solving the book’s main problem.

This is really tempting, by the way, if your story is ABOUT a young child. Who doesn’t want to help a little kid out? Don’t do it! If the kid is old enough to be a main character in a book for other kids – she’s old enough to get down from her own $#!% tree.

So here’s where the formula is wrong:

Act Three is where characters must get themselves down from the tree.

You don’t necessarily NEED to kill off a character’s parents to make him or her think independently and solve problems… but it sure helps.

Making orphans – for younger kids.

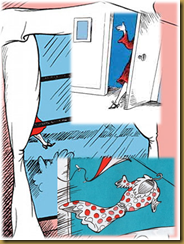

All the books I mentioned above are generally for older children. Because who wants to start a nice, light kiddie picture book with an image of parents lying in a coffin?

All the books I mentioned above are generally for older children. Because who wants to start a nice, light kiddie picture book with an image of parents lying in a coffin?

But if you’re writing for younger kids, there’s still hope. You just need to find ways to “kill” your parents without killing them.

Just get them out of the picture… without disturbing young readers.

Think about the Narnia books. The four children have parents, who are alive and perfectly healthy. But… conveniently, they’re somewhere else. They’re in London, and the first story (The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe) is set during World War 2, when children were sent out of London to the country due to German bombing raids.

Lewis has effectively (and very naturally) “killed” the children’s parents. It’s not that they don’t care about their kids, but they’re impotent to help the children or change the course of events in the story.

Yay! The makings of a great orphan story!

All we see of the mother are an empty dress, a hand, a rather stylish shoe. Things one might expect to see if one’s mother were… God forbid, dead.

One of the things I didn’t like about the movie version of The Cat in the Hat, by the way, is that the mother appears in the film. The rollicking adventures still take place… but with the mother in the picture, they take on a completely different tone.

Don’t make excuses.

Another lesson from Dr. Seuss: when your parents are gone, you don’t necessarily need to say where. It depends on your book. Because the world seems so very random to our kids, it may indeed be enough to say they’re “out for the day.” Or maybe they’re “at work” – the entire time the story takes place.

Another device works well in the Frances books (Bedtime for Frances, Baby Sister for Frances, etc), but it’s a little riskier. Her parents are physically there, usually sitting right in the living room, but they are usually doing that old-fashioned thing some parents today don’t know about: taking time for themselves. No excuses – they’re just not paying attention to her.

Another device works well in the Frances books (Bedtime for Frances, Baby Sister for Frances, etc), but it’s a little riskier. Her parents are physically there, usually sitting right in the living room, but they are usually doing that old-fashioned thing some parents today don’t know about: taking time for themselves. No excuses – they’re just not paying attention to her.

Frances’ dad reads the newspaper, her mom is busy with the baby. They still love Frances, but they’re happy enough to pursue their own interests and leave her up a tree if she gets there on her own. And she knows it well enough to solve her own problems.

Judging from my own kids, anyway, children are selfish critters. They’re not very interested in the specific things adults do when they’re apart, except as it concerns them (“did you bring me a present?”). Sometimes, all that registers with them is that you’re “out for the day”… it doesn’t matter where.

So don’t slow your story down explaining what’s up with mom and dad.

Instead of stepping in to rescue your characters – and creating boring stories, just follow this three-step “for the win” formula:

Step 1: Kill mom and dad (nonviolently, if you’re writing for little kids!).

Step 2: Get your character up a tree.

Step 3: Let him find his own $#! way down.

Got it? Sounds bossy, but I guarantee you, it works.

Time to share your own secrets! How do you “kill off” the parents, or at least, keep yourself from rescuing your characters from their trees??

Nice! I've been involved with a discussion where people are very concerned that we ought to be able to let kids solve things themselves without removing the parents. You show nicely that they needn't be dead, but they really do have to be out of the way (which is what I've been arguing--once there's a parent present, it's too much of a stretch to think they'd NOT step in to help).

ReplyDelete